This story was produced by Grist and co-published with Modern Farmer.

Standing knee-deep in an emerald expanse, a row of timber providing respite from the sweltering warmth, Rosa Morales diligently relocates chipilín, a Central American legume, from one mattress of soil to a different. The 34-year-old has been coming to the Campesinos’ Backyard run by the Farmworker Affiliation of Florida in Apopka for the final six months, taking residence a little bit of produce every time she visits. The small plot that hugs a soccer subject and group heart is an more and more important supply of meals to feed her household.

It additionally makes her consider Guatemala, the place she grew up surrounded by vegetation. “It jogs my memory of working the earth there,” Morales mentioned in Spanish.

Tending to the peaceable group backyard is a far cry from the harvesting Morales does for her livelihood. Ever since transferring to the USA 16 years in the past, Morales has been a farmworker at native nurseries and farms. She takes seasonal jobs that enable her the flexibleness and earnings to take care of her 5 youngsters, who vary from 18 months to fifteen years previous.

This yr, she picked blueberries till the season led to Could, incomes $1 for each pound she gathered. On a superb day, she earned about two-thirds of the state’s minimum hourly wage of $12. For that, Morales toiled in brutal warmth, with little in the best way of safety from the solar, pesticides, or herbicides. With scant water accessible, the danger of dehydration or warmth stroke was by no means removed from her thoughts. However these are the kinds of issues she should endure to make sure her household is fed. “I don’t actually have many choices,” she mentioned.

Now, she’s grappling with rising meals costs, a burden that isn’t relieved by state or federal security nets. Her husband works as a roofer, however as climate change diminishes crop yields and intensifies extreme weather, there’s been much less work for the 2 of them. They’ve struggled to cowl the hire, not to mention the household’s ballooning grocery bill.

“It’s laborious,” she mentioned. “It’s actually, actually scorching … the warmth is rising, however the salaries aren’t.” The Campesinos’ Garden helps fill within the hole between her wages and the price of meals.

Rosa Morales, left, and Amadely Roblero, proper, work within the Apopka backyard of their free time. Ayurella Horn-Muller / Grist

Her story highlights a hidden however mounting disaster: The very individuals who guarantee the remainder of the nation has meals to eat are going hungry. Though nobody can say for positive what number of farmworkers are meals insecure (local studies suggest it ranges from 52 to 82 percent), advocates are positive the quantity is climbing, driven in no small part by climate change.

The 2.4 million or so farmworkers who’re the spine of America’s agricultural trade earn among the many lowest wages in the country. The common American family spends more than $1,000 a month on groceries, an virtually unimaginable sum for households bringing residence as little as $20,000 a yr, particularly when meals costs have jumped more than 25 % since 2019. Grappling with these escalating prices will not be a problem restricted to farmworkers, after all — the Division of Agriculture says getting sufficient to eat is a monetary battle for more than 44 million people. However farmworkers are notably weak as a result of they’re largely invisible within the American political system.

“Once we speak about provide chains and meals costs going up, we aren’t interested by the people who find themselves producing that meals, or getting it off the fields and onto our plates,” mentioned Nezahualcoyotl Xiuhtecutli.

Xiuhtecutli works with the Nationwide Sustainable Agriculture Coalition to guard farmworkers from the occupational risks and exploitation they face. Few individuals past the employees themselves acknowledge that starvation is an issue for the group, he mentioned — or that it’s exacerbated by local weather change. The diminished yields that may comply with intervals of utmost warmth and the disruptions attributable to floods, hurricanes, and the like inevitably lead to less work, additional exacerbating the disaster.

There isn’t a number of assist accessible, both. Enrolling in federal help packages is out of the query for the roughly 40 percent of farmworkers without work authorization or for many who fear reprisals or sanctions. Even those that are entitled to such assist could also be reluctant to hunt it. In lieu of those sources, a rising variety of advocacy organizations are filling the gaps left by authorities packages by means of meals pantries, collaborative meals programs, and group gardens throughout America.

“Though [farmworkers] are doing this job with meals, they nonetheless have little entry to it,” mentioned Xiuhtecutli. “And now they’ve to decide on between paying hire, paying fuel to and from work, and utilities, or any of these issues. And meals? It’s not on the high of that record.”

A migrant employee works on a farm land in Homestead, Florida on Could 11, 2023. Chandan Khanna / AFP through Getty Photographs through Grist

∴

Traditionally, starvation charges amongst farmworkers, as with different low-income communities, have been at their worst during the winter as a result of inherent seasonality of a job that revolves around growing seasons. However climate change and inflation have made meals insecurity a growing, year-round problem.

In September, torrential rain brought on heavy flooding across western Massachusetts. The inundation decimated farmland already ravaged by a sequence of storms. “It impacted individuals’s skill to earn money after which have the ability to help their households,” Claudia Rosales mentioned in Spanish. “Individuals don’t have entry to primary meals.”

As government director of the Pioneer Valley Staff Middle, Rosales fights to increase protections for farmworkers, a group she is aware of intimately. After immigrating from El Salvador, she spent six years working in vegetable farms, flower nurseries, and tobacco fields throughout Connecticut and Massachusetts, and is aware of what it’s prefer to expertise meals insecurity. She additionally understands how different exploitative circumstances, corresponding to a scarcity of protecting gear or accessible loos, can add to the stress of merely attempting to feed a household. Rosales remembers how, when her children acquired sick, she was afraid she’d get fired if she took them to the physician as a substitute of going to work. (Employers harassed her and threatened to deport her if she tried to do something about it, she mentioned.) The necessity to put meals on the desk left her feeling like she had no selection however to tolerate the abuse.

“I do know what it’s like, how a lot my individuals undergo,” mentioned Rosales. “We’re not acknowledged as important … however with out us, there wouldn’t be meals on the tables throughout this nation.”

A younger woman carries a ‘We Feed You’ banner as she reveals help for farmworkers marching in opposition to anti-immigrant insurance policies within the Central Valley agriculture city of Delano, California, on April 2, 2017. Mark Ralston / AFP through Getty Photographs through Grist

The floodwaters have lengthy since receded and plenty of farms are as soon as once more producing crops, however labor advocates like Rosales say the area’s farmworkers nonetheless haven’t recovered. Federal and state catastrophe help helps those with damaged homes, businesses, or personal property, however does not typically support workers. Below federal law, if agricultural employees with a brief visa lose their job when a flood or storm wipes out a harvest, they are owed up to 75 percent of the wages they have been entitled to earlier than the catastrophe, alongside different bills. They aren’t all the time paid, nevertheless. “Final yr, there have been emergency funds due to the flooding right here in Massachusetts that by no means truly made it to the pockets of employees,” Rosales mentioned.

The warmth wave that lately scorched parts of Massachusetts possible reduced worker productivity and is poised to trigger more crop loss, additional limiting employees’ skill to make ends meet. “Local weather-related occasions affect individuals economically, and in order that then means restricted entry to meals and having the ability to afford primary wants,” mentioned Rosales, forcing employees to make troublesome choices on what they spend their cash on — and what they don’t.

The inconceivable selection between shopping for meals or paying different payments is one thing that social scientists have been learning for years. Analysis has proven, for instance, that low-income households usually buy less food during cold weather to keep the heat on. However local weather change has given rise to a new area to examine: how excessive warmth can set off caloric and nutritional deficits. A 2023 study of 150 international locations revealed that unusually scorching climate can, inside days, create larger dangers of meals insecurity by limiting the flexibility to earn sufficient cash to pay for groceries.

It’s a development Parker Gilkesson Davis, a senior coverage analyst learning financial inequities on the nonprofit Middle for Legislation and Social Coverage, is seeing escalate nationwide, notably as utility bills surge. “Households are undoubtedly having to grapple with ‘What am I going to pay for?’” she mentioned. “Individuals, on the finish of the month, will not be consuming as a lot, having makeshift meals, and never what we think about a full meal.”

Federal packages just like the Supplemental Diet Help Program, or SNAP, are designed to assist at occasions like these. Greater than 41 million people nationwide depend on the month-to-month grocery stipends, that are primarily based on earnings, household dimension, and a few bills. However one national survey of practically 3,700 farmworkers discovered simply 12.2 % used SNAP. Many farmworkers and migrant employees do not qualify due to their immigration standing, and those that do often hesitate to use the program out of fear that enrolling might jeopardize their standing. Even employees with momentary authorized standing like a working visa, or these thought of a “qualified immigrant,” usually should wait 5 years earlier than they’ll start receiving SNAP advantages. Simply six states present diet help to populations, like undocumented farmworkers, ineligible for the federal program.

Los Angeles Meals Financial institution employees put together packing containers of meals for distribution to individuals going through financial or meals insecurity amid the COVID-19 pandemic on August 6, 2020 in Paramount, California Mario Tama / Getty Photographs through Grist

The expiration of COVID-era profit packages, surging meals prices, and worldwide conflicts final yr compelled millions more Americans right into a state of meals insecurity, however nobody can say simply what number of are farmworkers. That’s as a result of such information is nearly nonexistent — though the Agriculture Division tracks annual national statistics on the issue. Lisa Ramirez, the director of the USDA’s Workplace of Partnerships and Public Engagement, acknowledged that the dearth of knowledge on starvation charges for farmworkers needs to be addressed on a federal stage and mentioned there’s a “need” to do one thing about it internally. However she didn’t make clear what particularly is being finished. “We all know that meals insecurity is an issue,” mentioned Ramirez, who’s a former farmworker herself. “I wouldn’t have the ability to level to statistics straight, as a result of I don’t have [that] information.”

With out that perception, little progress will be made to handle the disaster, leaving the majority of the issue to be tackled by labor and starvation reduction organizations nationwide.

“My guess is it might be the dearth of curiosity or will — kind of like a willful ignorance — to raised perceive and shield these populations,” mentioned social scientist Miranda Carver Martin, who research meals justice and farmworkers on the College of Florida. “A part of it’s only a ignorance on the a part of most of the people concerning the circumstances that farmworkers are literally working in. And that correlates to a scarcity of present curiosity or sources accessible to construct an proof base that displays these issues.”

The dearth of empirical data prevented Martin and her colleagues Amr Abd-Elrahman and Paul Monaghan from making a software that will establish the vulnerabilities native farmworkers expertise earlier than and after a catastrophe. “What we’ve discovered is that the software that we dreamed of, that will kind of comprehensively present all this information and mapping, will not be possible proper now, given the dearth of knowledge,” she famous.

Nonetheless, Martin and her colleagues did discover, in a forthcoming report she shared with Grist, that language barriers usually maintain farmworkers from getting assist after an excessive climate occasion. Inspecting the aftermath of Hurricane Idalia, they discovered circumstances of farmworkers in Florida attempting, and failing, to get meals at emergency stations as a result of so many employees spoke Spanish and directions have been written solely in English. She suspects the identical impediments might hinder post-disaster starvation reduction efforts nationwide.

Martin additionally believes there may be too little concentrate on the difficulty, partially as a result of some politicians demonize immigrants and the agriculture trade depends upon cheap labor. It’s simpler “to fake that these populations don’t exist,” she mentioned. “These inequities must be addressed on the federal stage. Farmworkers are human beings and our society is treating them like they’re not.”

A warming world is one amplifying menace America’s farmworkers are up in opposition to, whereas a rising anti-immigrant rhetoric mirrored in exclusionary insurance policies is one other. Ayurella Horn-Muller / Grist

∴

Tackling starvation has emerged as one of many largest priorities for the Pioneer Valley Staff Middle that Claudia Rosales leads. Her crew feeds farmworker households in Massachusetts by way of La Despensa del Pueblo, a meals pantry that distributes meals to roughly 780 individuals every month.

The nonprofit launched the pantry within the winter of 2017. When the pandemic struck, it quickly developed from a makeshift meals financial institution into a bigger operation. However this system ran out of cash final month when a key state grant expired, sharply curbing the quantity of meals it might distribute. The rising must feed individuals additionally has restricted the group’s skill to concentrate on its main objective of group organizing. Rosales desires to see the meals financial institution give method to a extra entrepreneurial mannequin that provides farmworkers better autonomy.

“For the long run, I’d prefer to create our personal community of cooperatives owned by immigrants, the place individuals can go and develop and harvest their very own meals and merchandise and actually have entry to producing their very own meals after which promoting their meals to of us inside the community,” she mentioned.

Mónica Ramírez, founding father of the nationwide advocacy group Justice for Migrant Girls, is creating one thing very very like that in Ohio. Ramírez herself hails from a farmworker household. “Each of my dad and mom began working within the fields as youngsters,” she mentioned. “My dad was eight, my mother was 5.” Rising up in rural Ohio, Ramírez remembers visiting the one-room shack her father lived in whereas selecting cotton in Mississippi, and spending time along with her grandparents who would “pile on a truck” every year and drive from Texas to Ohio to reap tomatoes and cucumbers all summer time.

The challenges the Ramírez household confronted then persist for others right this moment. Meals safety has grown so tenuous for farmworkers in Fremont, Ohio, the place Justice for Migrant Girls relies, that the group has gone past collaborating with organizations like Feeding America to design its personal hyperlocal meals system. These starvation reduction efforts are targeted on girls locally, who Ramírez says often face the biggest burdens when a family doesn’t manage to pay for for meals.

Migrant girls, she mentioned, “bear the stress of financial insecurity and meals insecurity, as a result of they’re those who’re organizing their households and ensuring their households have meals in the home.”

Later this month, Ramírez and her crew will launch a pilot program out of their workplace that mimics a farmers market — one through which farmworkers and migrant employees shall be inspired to select up meals offered by an area farmer, at no cost. That permits these visiting the meals financial institution to really feel empowered by selection as a substitute of being handed a field with preselected items, they usually hope it should alleviate starvation in a means that preserves a way of company for households in want.

Though federal lawmakers have begun at the very least considering defending employees from warmth publicity and regulators are making progress on a national heat standard, up to now there’s been no focused legislative or regulatory effort to handle meals insecurity amongst farmworkers.

In reality, legislators could also be on the verge of creating issues worse.

In Could, the Republican-controlled U.S. Home of Representatives Agriculture Committee handed a draft farm invoice that will gut SNAP and do little to promote food security. It additionally would bar state and native governments from adopting farmworker safety requirements regulating agricultural manufacturing and pesticide use, echoing legislation Florida recently passed. The inclusion of such a provision is “disappointing,” mentioned DeShawn Blanding, a senior Washington consultant on the Union of Involved Scientists, a nonprofit advocacy group. He hopes to see the model that finally emerges from the Democrat-controlled Senate, the place it remains stalled, incorporate a number of different proposed payments geared toward defending farmworkers and offering a measure of meals safety.

These embrace the Voice for Farm Workers Act, which might shore up funding for a number of established farmworker help initiatives and increase sources for the Agriculture Division’s farmworker coordinator. This place was created to pinpoint challenges faced by farmworkers and join them with federal sources, however it has not been “adequately funded and sustained,” in accordance with a 2023 USDA Equity Commission report. Another bill would create an office within the Agriculture Department to behave as a liaison to farm and meals employees.

These payments, launched by Democratic Senator Alex Padilla of California, would give lawmakers and policymakers better visibility into the wants and experiences of farmworkers. However the biggest profit might come from a 3rd proposal Padilla reintroduced, the Fairness for Farm Workers Act. It will reform the 1938 law that governs the minimal wage and time beyond regulation insurance policies for farmworkers whereas exempting them from labor protections.

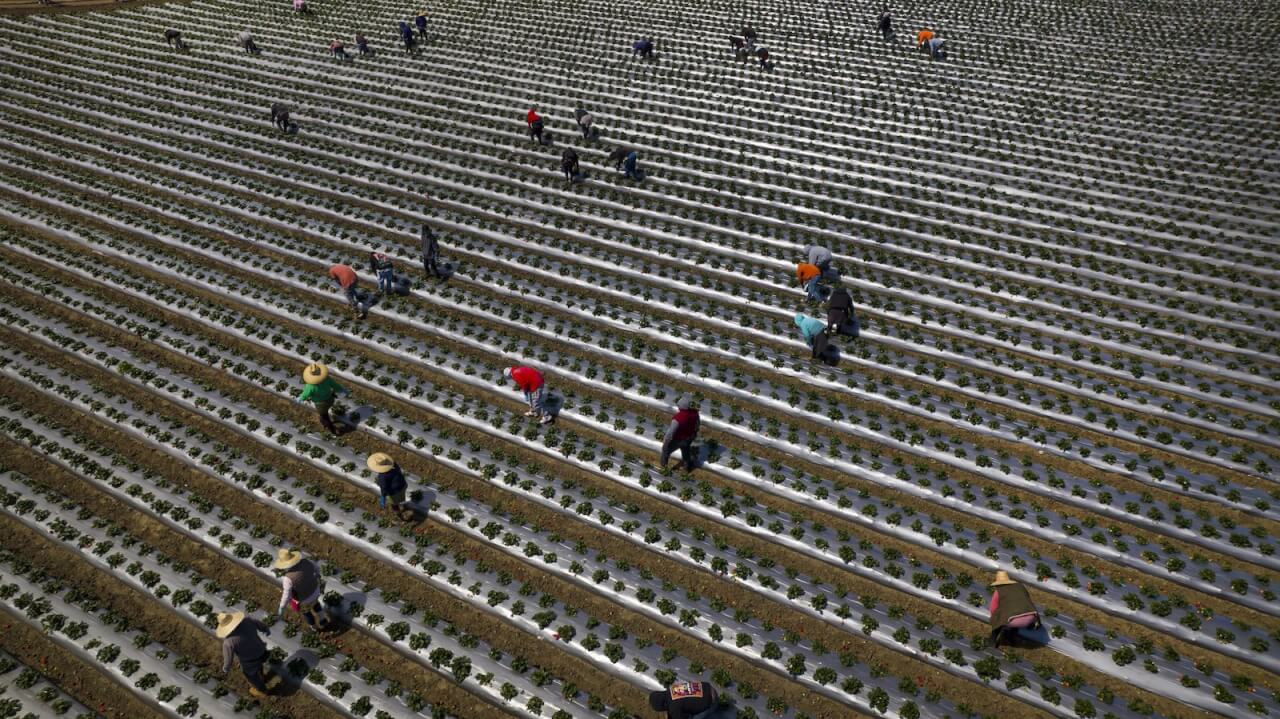

Migrant employees decide strawberries throughout harvest south of San Francisco in April 2024. Visions of America / Joe Sohm / Common Photographs Group through Getty Photographs through Grist

“As meals costs enhance, low-income employees are going through better charges of meals insecurity,” Padilla advised Grist. “However roughly half of our nation’s farmworkers are undocumented and unable to entry these advantages.” He’d prefer to see an expedited pathway to citizenship for the over 5 million important employees, together with farmworkers, who lack entry to everlasting authorized standing and social security advantages. “Extra will be finished to handle rising meals insecurity charges for farmworkers.”

Nonetheless, none of those payments squarely addresses farmworker starvation. And not using a concerted method, these efforts, although vital, form of miss the purpose, Mónica Ramírez mentioned.

“I simply don’t suppose there’s been a superb level on this difficulty with meals and farmworkers,” she mentioned. “To me it’s form of ironic. You’d suppose that will be a place to begin. What’s going to it take to guarantee that the people who find themselves feeding us, who actually maintain us, will not be themselves ravenous?”

∴

For 68-year-old Jesús Morales, the Campesinos’ Backyard in Apopka is a second residence. Drawing on his background learning various drugs in Jalisco, Mexico, he’s been serving to have a tendency the land for the final three years. He notably likes rising and harvesting moringa, which is utilized in Mexico to deal with a variety of illnesses. Common guests know him because the “plant physician.”

“Go searching. That is the reward of God,” Morales mentioned in Spanish. “This can be a meadow of hospitals, a meadow of medicines. Every part that God has given us for our well being and well-being and for our happiness is right here, and that’s a very powerful factor that we’ve right here.”

Jesús Morales views vegetation like moringa, which is utilized in Mexico to deal with a variety of illnesses, as “the reward of God.” Ayurella Horn-Muller / Grist

He got here throughout the headquarters of the state farmworker group when it hosted free English courses, then discovered about its backyard. Though it began a decade in the past, its goal has expanded through the years to change into a supply of food security and sovereignty for native farmworkers.

The half-acre backyard teems with a staggering assortment of produce. Tomatoes, lemons, jalapeños. Close by timber provide dragonfruit and limes, and there’s even a smattering of papaya vegetation. The air is thick with the odor of freshly dug soil and hints of herbs like mint and rosemary. Two compost piles sit aspect by aspect, and a greenhouse bursts with nonetheless extra produce. Anybody who visits throughout bi-monthly public gardening days is inspired to plant their very own seeds and take residence something they care to reap.

“The individuals who come to our group backyard, they take buckets with them after they can,” mentioned Ernesto Ruiz, a analysis coordinator on the Farmworker Affiliation of Florida who oversees the backyard. “These are households with six children, they usually work poverty wages. … They love working the land they usually love being on the market, however meals is a large incentive for them, too.”

All through the week, the nonprofit distributes what Ruiz harvests. The produce it so readily shares is supplemented by common donations from native supermarkets, which Ruiz usually distributes himself.

However a number of the identical elements driving farmworkers to starvation have begun to encroach on the backyard. Blistering summer time warmth and earlier, hotter springs have worn out crops, together with a number of plots of tomatoes, peppers, and cantaloupes. “A variety of vegetation are dying as a result of it’s so scorching, and we’re not getting rains,” mentioned Ruiz. The backyard might additionally use new tools — the irrigation system is guide whereas the weed whacker is third-rate, usually swapped out for a machete — and funding to rent one other individual to assist Ruiz enhance the quantity of meals grown and increase when the backyard is open to the general public.

Demand is rising, and with it, strain to ship. Federal laws addressing the low wages that result in starvation for a lot of farmworkers throughout the nation is an enormous a part of the answer, however so are community-based initiatives just like the Campesinos’ Backyard, in accordance with Ruiz. “You do the precise factor as a result of it’s the precise factor to do,” he mentioned. “It’s all the time the precise factor to feed anyone. All the time.”

Ernesto Ruiz, pictured, oversees the Farmworker Affiliation of Florida’s backyard in Apopka. Ayurella Horn-Muller / Grist

Trending Merchandise